JAMES KANE, IRENE KANE, DONALD MANN, GERALDINE MANN, and CROW POINT COMMUNITY CLUB v. ROBERT STIMSON, CYNTHIA STIMSON, MICHAEL DONAHUE, MARY DONAHUE, and AMYRA O'CONNELL, Defendants.

JAMES KANE, IRENE KANE, DONALD MANN, GERALDINE MANN, and CROW POINT COMMUNITY CLUB v. ROBERT STIMSON, CYNTHIA STIMSON, MICHAEL DONAHUE, MARY DONAHUE, and AMYRA O'CONNELL, Defendants.

MISC 04-302869

August 3, 2016

SANDS, J.

THIRD REVISED DECISION

Introduction

This case, a long-running dispute between neighbors in the picturesque seaside village of Crow Point in Hingham, can be summed up with a quote:

Over a century and a half ago, Herman Melville noted the irresistible attraction that the seashore holds for our species: But look! here come more crowds, pacing straight for the water, and seemingly bound for a dive. Strange! Nothing will content them but the extremist limit of land . . . . No. They must get just as near the water as they possibly can without falling in. And there they stand-miles of them- leagues! Inlanders all, they came from lanes and alleys, streets and avenues-north, east, south, and west. Yet here they all unite. Tell me, does the magnetic virtue of the needles of the compasses of all these ships attract them thither? Melville, Moby Dick 2 (Great Books of the Western World ed.1948) (1851).

Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 175-176 (1998). It is particularly apt to quote Melville here, as the case involves land formerly owned by a relative of his and a right of way named in honor of his family. [Note 2]

More specifically, this is a dispute between neighbors regarding who among them have rights to use and access a beach on Hingham Harbor (the Disputed Beach) [Note 3] via a private right of way known as Melville Walk. The procedural history of the litigation dates back over a decade, and this courts decisions have been appealed multiple times. [Note 4]

My original Decision (Land Court Decision 1) and Judgment (the Judgment) issued on December 12, 2007. On November 14, 2008, I issued a Revised Decision (Land Court Decision 2) and Revised Judgment (the First Amended Judgment), giving legal effect to an agreement among a number of the parties as to the use of the Disputed Beach. Several parties on both sides of the dispute appealed to the Appeals Court. By decision of the Appeals Court dated February 16, 2011 (Appeals Court Decision 1), the Appeals Court reversed and vacated portions of Land Court Decision 1 and Land Court Decision 2. [Note 5] See generally Kane v. Vanzura, 78 Mass. App. Ct. 749 (2011), rev. denied, 460 Mass. 1104 (2011). [Note 6]

On remand, due to the absence of the estate (the Downer Estate) of the late Samuel Downer (Downer), who died in 1881, as a party to this case, I issued a Second Revised Decision (Land Court Decision 3) and Second Amended Judgment (the Second Amended Judgment) dated May 16, 2014, holding, inter alia, that I could not adjudicate any rights under the May 1929 Deed (defined in Land Court Decision 1 as a deed dated May 14, 1929, and recorded in the Plymouth County Registry of Deeds (the Registry) at Book 1575, Page 195) unless the Downer Estate were to be brought into the case as a party. Several parties again appealed to the Appeals Court. By decision dated September 1, 2015 (Crow Point Cmty. Club v. Martel, 88 Mass. App. Ct. 1103 (2015) (Appeals Court Decision 2)), the Appeals Court reversed Land Court Decision 3 and the Second Amended Judgment, and directed that this court can, and should, resolve the issues of identity and rights of the [Deeded Rights Plaintiffs, defined infra] without the Downer Estate as a party, explaining that [i]nterpretation of the deed is a matter of law and does not require evidence to be taken unless the meaning of an essential term or phrase is ambiguous. [Note 7]

The matter now comes before me again on remand from the Appeals Court for determination of several remaining matters. Following Appeals Court Decision 2, there are only three questions remaining for me to adjudicate. First, I must determine which of the parties defined as the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs in Amended Appeals Court Decision 1 have rights in the Disputed Beach and Melville Walk, as opposed to merely claiming such rights. Second, I must determine the scope of those rights in Melville Walk. Third, I must determine the scope of those rights in the Disputed Beach.

Facts and Procedural History

This case was originally filed in Plymouth County Superior Court (Case Number PLCV2004- 00828) on June 29, 2004 by Plaintiffs James and Irene Kane (the Kanes), Donald and Geraldine Mann (the Manns), and the Crow Point Community Club (the Community Club) as a declaratory judgment action on the issue of whether those Plaintiffs (whose properties were located inland from the Disputed Beach and Melville Walk) had deeded easement rights to use Melville Walk to access and use the Disputed Beach. [Note 8] In the alternative, they sought a declaratory judgment that they had a prescriptive access easement to use Melville Walk to access the Disputed Beach. The initially-named Defendants were Robert and Cynthia Stimson (the Stimsons), Michael and Mary Donahue (the Donahues), and Amyra OConnell (OConnell), whose properties all abutted Melville Walk. In their answers, Defendants disputed not only Plaintiffs rights in Melville Walk, but also challenged Plaintiffs rights to use the Disputed Beach itself. On October 18, 2004, the case was transferred to the Land Court and assigned the above-captioned Miscellaneous Case No. 302869 (the Miscellaneous Case). [Note 9] From the time the Miscellaneous Case was commenced and the case went to trial, several parties were dismissed from the case, and a number of new parties were added, as their interests in this matter became more apparent. [Note 10]

After a site view and trial held on August 9-11, 2006, I issued Land Court Decision 1 and the Judgment on December 12, 2007. Before getting to my holdings in Land Court Decision 1, however, it will be important to reiterate a few terms defined therein regarding the properties and ways at issue.

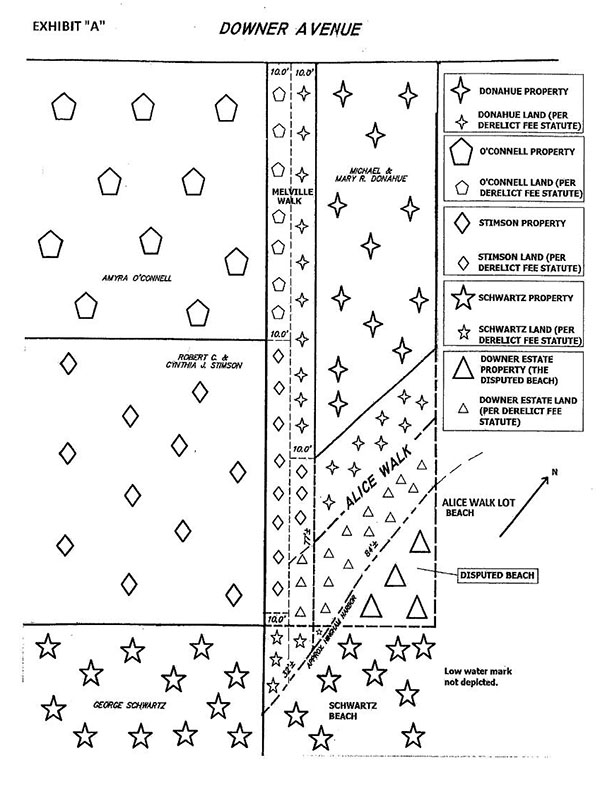

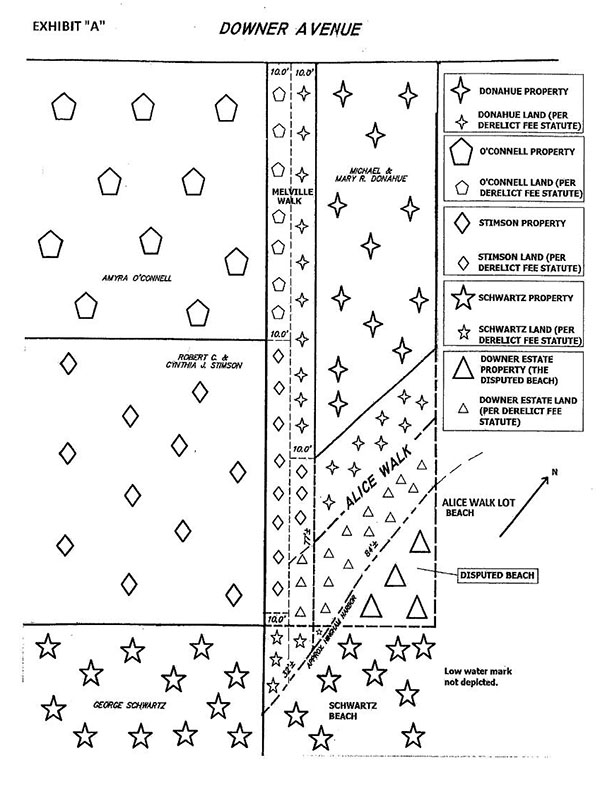

Land Court Decision 1 makes references to (and defines as the 1897 Plan) a compilation plan entitled Land at Crow Point, Hingham, Mass. Belonging to Estate of Samuel Downer, dated April 12, 1897, prepared by Ernest W. Bowditch, and recorded in the Registry at Plan Book 1, Page 186. The 1897 Plan depicts hundreds of subdivided lots that comprised a large tract of land owned by the Downer Estate (the Downer Tract), including all of the parties properties at issue in this case, the Disputed Beach, Melville Walk, and Alice Walk (defined, infra).

As discussed in Land Court Decision 1, Defendants properties are shown on the 1897 Plan as follows:

(a) the Donahue Property: lots 1" and 2" on the 1897 Plan;

(b) the OConnell Property: lots 100" and 101" on the 1897 Plan;

(c) the Stimson Property: lots 102", 103", and the northerlyfive feet of lot 104" on the 1897 Plan; and,

(d) the Schwartzes Property: the remainder of lot 104", all of lot 105", all beaches and flats on the seaward side of lots 104" and 105" (the Schwartz Beach), and several additional lots on the westerly side of Causeway Street, which lots 104" and 105" abut on its easterly side (the Schwartz Property). [Note 11]

Plaintiffs properties are also depicted on the 1897 Plan, located to the north and west, most on the northerly side of Downer Avenue. The 1897 Plan also depicts, to the east of the Donahue Property, five lots numbered 3" through 7", which are owned jointly, together with the fee in Alice Walk and the beaches and flats (the Alice Walk Beach) to which they are adjacent (together, the Alice Walk Lot). [Note 12] The owner of the Alice Walk Lot is not a party to this case, and no rights in any portion of the Alice Walk Lot are presently in dispute in this case, but the lot itself is important in terms of its relationship with the parties lots that are at issue.

In Land Court Decision 1, I described the Disputed Beach (defined there simply as the Beach) as follows:

On the west by Melville Walk and the portion of Alice Walk [defined infra] abutting the Donahue Property, on the south by the Schwartz Property [defined infra], on the east by Hingham Harbor, and on the north by Alice Walk and the land of the owners of lots 3-7 as shown on the 1897 Plan. The [Disputed] Beach is separated from the Schwartz Property on the south end by a row of rocks. On the north end and west end, it is marked by sea grass and a sea wall, and contains both a lower beach and an upper beach. The upper beach contains a picnic table with two attached benches, and the lower beach contains large logs used as benches. On the east end the [Disputed] Beach extends to the mean low water line of Hingham Harbor. [Note 13]

I defined Melville Walk as follows:

Melville Walk is also shown on plan titled Plan of Land Melville Walk in Hingham, MA dated October 18, 2004 and prepared by Aaberg Associates Inc. (the 2004 Plan). The 2004 Plan shows Melville Walk as twenty feet in width, 160 feet in length from Downer Avenue, a public way, to the intersection with Alice Walk, a private way, and 227.32 feet in length from Downer Avenue to the intersection of the Stimson Property and the Schwartz Property. [Note 14]

Land Court Decision 1 did not specifically define Alice Walk, but did discuss it at length and made numerous findings of fact about it. It is a private way, and is shown on the 1897 Plan as running from Downer Avenue southwesterly along the beach-facing lot lines of the Alice Walk Lot and the Donahue Lot to its intersection with Melville Walk. [Note 15]

In order to be as precise as possible as to the location of the Disputed Beach and the surrounding properties, ways, and beaches, and to minimize any ambiguity or confusion that might have arisen due to the different ways they have been described in this case, I have annexed as Exhibit A hereto a plan depicting the Disputed Beach and surrounding properties and ways. As shown on Exhibit A, the Disputed Beach is the triangular area of beach on the seaward side of Alice Walk, across from the Donahue Property. It is bounded as follows: (a) by the seaward edge of Alice Walk (which also appears to be the mean high water mark) [Note 16] between the side lot lines of the Donahue Property, (b) by the easterly edge of the Alice Walk Beach (which, as noted, forms part of the Alice Walk Lot and extends to the mean low water line, and (c) by the northerly edge of the Schwartz Beach (which, as noted, forms part of the Schwartz Property and extends to the low water line). [Note 17] Having defined these terms, I turn to Land Court Decision 1, in which I found and ruled, inter

alia, as follows:

(a) that none of Plaintiffs have obtained rights in the [Disputed] Beach as a result of the Downer-Cushing Indenture,

Judgment at 3; [Note 18]

(b) that the Donahues own the fee interest in the [Disputed] Beach [Note 19], and the May 1929 Deed did not grant any rights in the [Disputed] Beach, Judgment at 3;

(c) that by March of 1920, the Downer Estate had deeded away the entire portion of Melville Walk and Alice Walk from Downer Avenue to the [Disputed] Beach, and they had nothing left to deed out to others, Judgment at 3; [Note 20]

(d) that Plaintiffs do not have implied easements to use either the [Disputed] Beach or Melville Walk, Judgment at 3;

(e) that there is no easement by estoppel in Melville Walk for the benefit of Plaintiffs, Judgment at 3-4;

(f) that Defendants Motion for Directed Verdict . . . against Plaintiffs Cates/Malcolm, the McCourts, the Maslands, the Coxes, and Patrolia/Callahan with respect to prescriptive rights in both the [Disputed] Beach and Melville Walk was allowed because they did not present evidence at trial, Judgment at 4;

(g) that Plaintiffs Iser, Dow and Ponder have failed to establish prescriptive rights because they could not show twenty consecutive years of use of either the [Disputed] Beach or Melville Walk, Judgment at 4;

(h) that Defendants, their predecessors, or the Donahues in particular, did not give permission to Plaintiffs for use of the [Disputed] Beach or Melville Walk, Judgment at 4;

(i) that the Manns, the Dillons [Note 21], the Arnolds, Campbell, the Kanes, Handrahan, and the Murrays have established prescriptive rights in both the southerly portion of Melville Walk [Note 22] for access to the [Disputed] Beach, and the [Disputed] Beach for uses consistent with the uses established by them over the last quarter to half century, [Note 23] Judgment at 4; and,

(j) that Defendants must remove the Gate and any impediments to access over both the southerly portion of Melville Walk and the [Disputed] Beach, Judgment at 4.

Following the issuance of Land Court Decision 1, the parties filed various motions and amended motions seeking to clarify, amend, alter, vacate, and/or reconsider the Judgment. [Note 24] In an effort to resolve the parties disagreements as to how to implement Land Court Decision 1, on July 18, 2008, the Prescriptive Rights Plaintiffs [Note 25], the Schwartzes, and the Donahues filed a joint report (the Joint Report) in which they agreed to define the area of the Disputed Beach (which they defined as the Permitted Beach), as well as its uses, and the parties with rights in the Disputed Beach and Melville Walk. [Note 26] The Stimsons did not join in the Joint Report, instead filing opposition to it, which proposed different definitions of the area of the Disputed Beach, its uses, and the parties with rights in the Disputed Beach and Melville Walk.

Despite their best efforts, the parties were unable to resolve this disagreement among themselves. Thus, to resolve this stalemate, on November 14, 2008, this court issued Land Court Decision 2 and the First Amended Judgment, which amended Land Court Decision 1 to give effect to the agreement of the parties to the Joint Report to redefine the Disputed Beach as the Permitted Beach and to redefine the scope and extent to which the Permitted Beach could be used by the Prescriptive Rights Plaintiffs. [Note 27] Except as expressly modified by Land Court Decision 2, however, the remainder of Land Court Decision 1 remained unchanged. [Note 28]

In December of 2008, a number of the parties appealed Land Court Decision 2 and the First Amended Judgment to the Appeals Court. [Note 29] On February 16, 2011, the Appeals Court issued Appeals Court Decision 1, which reversed in part, affirmed in part, and vacated in part Land Court Decisions 1 and 2. The Appeals Courts holdings are discussed, infra.

In response to Appeals Court Decision 1, the parties filed a petition for rehearing of the appeal, arguing, among other things, that Appeals Court Decision 1 contained certain transcription errors. By order dated March 28, 2011, the Appeals Court denied that petition, but made several modifications to Appeals Court Decision 1, as follows:

The petition for rehearing is denied. We order changes to our opinion of February 16, 2011, as follows. The following sentence is added to the end of footnote five: Because the judge concluded that the 1929 instrument was ineffective to convey any rights in the beach and the ways, he did not reach or consider any other question that may exist concerning the claims of the deeded rights plaintiffs to rights derived from the 1929 instrument, and we decline to undertake such a determination in the first instance. We delete the last sentence of the last paragraph under Discussion, a. Deeded rights. [Note 30] Footnote sixteen shall now follow what had been the penultimate sentence. We strike the second sentence of the paragraph under Conclusion [Note 31] and substitute the following sentence: The case is remanded to the Land Court for determination of the rights held by the deeded rights plaintiffs. The phrase and the beach is deleted from the penultimate sentence under Conclusion. [Note 32] In all other respects the opinion remains the same.

In accordance with this order, the Appeals Court issued its Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, which was filed with this court on June 16, 2011.

On the issue of deeded rights conveyed by the May 1929 Deed, Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, inter alia, held as follows:

Contrary to the conclusion of the judge, the 1897 conveyance of the Donahue property under a deed description bounded on Melville Walk and Alice Walk did not operate to divest the estate of Samuel Downer of its fee interest in the beach and tidelands on the seaward side of those ways, its fee interest to the portion of Alice Walk southeast of its centerline, or its right to use Melville Walk as a means of access to the beach and tidelands. Accordingly, at the time of its 1929 conveyance of rights to use the beach and the ways, the estate of Samuel Downer held the rights it purported to convey by that instrument.

Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 757. Accordingly, the court held, [t]he judgment is reversed insofar as it declares that the Donahues own the fee interest in the beach . . . . Id. at 759. [Note 33]

Having found that the Downer Estate had held the rights it purported to convey by [the 1929 Deed], the court continued, finding that [t]he subsequent intent of the Downer estate to convey (by means of the 1929 instrument on which the plaintiffs base their claim) the right to use Melville Walk and the beach is manifest by the express terms of the instrument. Id. at 756, n. 14. Thus:

We conclude that the judge erred in his conclusion that a 1929 instrument, purporting to convey rights of access to, and use of, the beach, was invalid because the grantor previously had divested all of its interest in the beach (and access ways) by operation of law. We accordingly reverse the judgment insofar as it declared that the plaintiffs claiming deeded rights do not hold the right to use the way.

Id. at 750.

In sum, on the issue of deeded rights, [t]he judgment is reversed insofar as it declares that

. . . the 1929 deed conveyed no rights in the beach or Melville Walk to the deeded rights plaintiffs [and] that the deeded rights plaintiffs hold no easement rights in Melville Walk . . . . Id. at 759; see also id. at 751, n. 5 (defining the deeded rights plaintiffs as the plaintiffs claiming rights under the 1929 Downer deed, to wit: the Kanes, the Manns, Ponder, Dow, the Coxes, Patrolia and Callahan, and the Arnolds (together, the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs). [Note 34]

Regarding the issue of prescriptive rights, the Appeals Court concluded that [b]ecause the parties to this action do not include the holder of the record interest in the beach, we vacate the judgment insofar as it adjudicated rights in the beach itself. Id. at 750. However, [t]he judgment is affirmed insofar as it declares that the prescriptive rights plaintiffs have established prescriptive rights in the southerly portion of Melville Walk. Id. at 759. [Note 35] In addition, [t]he judgment is reversed insofar as it declares that . . . certain of the deeded rights plaintiffs have acquired prescriptive rights to use Melville Walk and the beach. Id. at 759. [Note 36] Finally, [t]he judgment is [ ] affirmed insofar as it dismisses the claims of the remaining plaintiffs. Id. at 759. [Note 37] Thus, the Appeals Court remanded the case for the determination of the rights held by the deeded rights plaintiffs. Id. [Note 38]

On remand, the parties attempted to reach an agreement regarding a proposed final disposition of the case, implementing Amended Appeals Court Decision 1. Their efforts proved unsuccessful, so the court directed the parties to file dispositive motions outlining their respective positions. [Note 39] After the parties had briefed summary judgment motions, this court called a status conference on October 28, 2013, at which I expressed the view that no further dispositive action could be taken relative to the Disputed Beach unless and until the Downer Estate was brought in as a party. However, based upon alleged difficulties with identifying, locating, and notifying potential members of the Downer Estate, Plaintiffs informed the court that they would be unable to amend their complaint to add the Downer Estate as a Defendant. [Note 40] In view of this representation, on May 16, 2014, I issued Land Court Decision 3 and the Second Amended Judgment, holding, inter alia, that I could not adjudicate any rights under the May 1929 Deed unless the Downer Estate were to be brought into the case as a party, because due process required that the owner of the Disputed Beach has the right to weigh in on who has rights in its Beach.

Plaintiffs and Defendants the Martels and Schlosberg each appealed Land Court Decision 3 and the Second Amended Judgment. On September 1, 2015, the Appeals Court [Note 41] issued Appeals Court Decision 2, which directed that this court can, and should, resolve the issues of identity and rights of the [Deeded Rights Plaintiffs] without the Downer Estate as a party, Appeals Court Decision 2, 88 Mass. App. Ct. at 1103, *2, explaining that [i]nterpretation of the deed is a matter of law and does not require evidence to be taken unless the meaning of an essential term or phrase is ambiguous, id. (emphasis added). [Note 42] Appeals Court Decision 2 further held that [w]e vacate the portion of the second amended judgment declining to adjudicate any rights under the 1929 deed unless the Downer estate is added as a party. We remand for further proceedings consistent with this memorandum and order. Id. at 1103, *3. [Note 43]

On remand to this court once again, I directed the parties to brief motions outlining their respective positions as to the courts final remand judgment and the remaining issues to be resolved thereby. The parties briefs were filed in October and November of 2015, and at that time the matter was again taken under advisement.

Discussion

The only issues left to adjudicate in this case are now the rights of the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs, as all other parties claims have now been fully and finally adjudicated. [Note 44] As discussed, supra, in Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, the Appeals Court found that because, (a) at the time of its 1929 conveyance of rights to use the beach and the ways, the estate of Samuel Downer held the rights it purported to convey by that instrument, and (b) [t]he subsequent intent of the Downer estate to convey (by means of the 1929 instrument on which the plaintiffs base their claim) the right to use Melville Walk and the beach is manifest by the express terms of the instrument, the 1929 instrument validly conveyed rights to use the beach and ways, and, therefore [t]he judgment is reversed insofar as it declares that . . . the 1929 deed conveyed no rights in the beach or Melville Walk to the deeded rights plaintiffs [and] that the deeded rights plaintiffs hold no easement rights in Melville Walk . . . . [Note 45]

It now remains for this court only to resolve such other question[s] that mayexist concerning the claims of the deeded rights plaintiffs to rights derived from the 1929 instrument, [as to which the Appeals Court decline[d] to undertake such a determination in the first instance, namely: (a) which of the parties defined by the Appeals Court as the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs not only claim, but actually have deeded easement rights in Melville Walk and the Disputed Beach pursuant to the May 1929 Deed, and (b) the proper scope of those rights in Melville Walk and (c) the Disputed Beach. [Note 46] I shall address each of these issues in turn.

The Identity of the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs

As discussed, supra, the Appeals Court defined the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs as those Plaintiffs claiming deeded rights under the May 1929 Deed, to wit: the Kanes, the Manns, Ponder, Dow, the Coxes, Patrolia and Callahan, and the Arnolds. [Note 47] The Deeded Rights Plaintiffs argue that they all have rights under the May 1929 Deed. Defendants disagree. They contend that only the Kanes, the Arnolds successor owners (Flaherty and Whelan), and Patrolia and Callahan have such rights because, they argue, the properties now or formerly owned by the Manns (now owned by Robin and Cavanaugh), Ponder (now owned by the Annellos), Dow, and the Coxes were not owned by a named grantee of the May 1929 Deed at the time that deed was executed and recorded. On this basis, they thus seek to exclude these Plaintiffs (and their lots) from the class of beneficiaries of the May 1929 Deed. [Note 48] In other words, they seek to draw a distinction between those parties claiming rights (per the language of Amended Appeals Court Decision 1) from those who actually have such rights. [Note 49]

Appeals Court Decision 2 provides multiple indications that the Appeals Court intended to leave it to this court to determine whether all of the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs actually have the deeded rights that they claim. For instance, the Appeals Court specifically references defendants . . . arguments on the identity of the deeded rights plaintiffs (involving chain of title issues), Appeals Court Decision 2, 88 Mass. App. Ct. at 1103, *2, n. 6, but decline[s] to consider such arguments until the judge has made such determinations in the first instance. Id. Furthermore, in determining that this court should proceed without the Downer estate as a party, the Appeals Court describes the issues to be determined as resolv[ing] the issues of identity and rights of the deeded rights plaintiffs. Id. at 1103, *2. Moreover:

To the extent that the judge, on remand, considers issues raised by the defendants that some of the deeded rights plaintiffs are actually outside the chain of title from the 1929 deed, and therefore do not have any rights under that instrument, the judge may consider any appropriate evidence from the parties.

Id. at 1103, *2, n. 7.

It is difficult to square Amended Appeals Court Decision 1 with Appeals Court Decision 2. On the one hand, the former clearly states that [w]e accordingly reverse the judgment insofar as it declared that the plaintiffs claiming deeded rights do not hold the right to use the way. Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 750 (emphasis added). Yet, on the other, the latter specifically instructs this court, on remand, to resolv[e] the issues of identity and rights of the deeded rights plaintiffs. Appeals Court Decision 2, 88 Mass. App. Ct. at 1103, *2. I interpret Appeals Court Decision 2 to mean that the Appeals Court did, in fact, intend to leave it to this court to consider -- as one of the other question[s] that may exist concerning the claims of the deeded rights plaintiffs -- whether all of the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs actually have such deeded rights. [Note 50] I thus turn to that question, which requires an analysis of several deeds in the record.

Pursuant to the March 1929 Deed (defined in Land Court Decision 1 as the deed dated March 5, 1929 and recorded in the Registry at Book 1569, Page 446), George A. Cole (Cole) deeded to William Daley (Daley) a parcel of land (formerly part of the Downer Tract) described as lot 3" on a plan of land entitled Plan of Subdivision of Land at Crow Point Hingham, Mass., dated February 25, 1929, prepared by Russell H. Whiting, and recorded in the Registry at Plan Book 4, Page 862 (the February 25, 1929 Plan). [Note 51] Concurrently with the March 1929 Deed, Daley granted a mortgage (also recorded at Book 1569, Page 446) (the White Mortgage) in the property conveyed by the March 1929 Deed to William E. White, trustee of the Downer Estate (White). [Note 52]

This lot 3" on the February 25, 1929 Plan was then subdivided into lots A through P in a subsequent subdivision plan entitled Plan of Subdivision of Land at Crow Point Hingham, Mass., dated February 28, 1929, prepared by Russell H. Whiting, and recorded in the Registry at Plan Book 4, Page 623 (the February 28, 1929 Plan). [Note 53] Then, by deed dated April 11, 1929, and recorded in the Registry at Book 1572, Page 328 (the April 1929 Deed), Daley deeded to Thomas J. Higgins (Higgins) lots J through P, as shown on the February 28, 1929 Plan. [Note 54] In connection with the April 1929 Deed, Higgins granted back to Daley a mortgage dated April 11, 1929 and recorded in the Registry at Book 1572, Page 329 upon lots K through P (the Daley Mortgage), leaving only lot J unencumbered. [Note 55] Higgins soon thereafter deeded lot J to Frank and Leota Reed (the Reeds) by deed dated May 16, 1929 and recorded in the Registry at Book 1575, Page 150 (the Reed Deed) -- only four days prior to the recording of the May 1929 Deed.

Mere days later, by the May 1929 Deed, White, acting as trustee of the Downer Estate, granted:

to [Daley], and to those claiming under him as their respective interests may appear as appurtenant to the land on Downer Avenue and Jarvis Avenue in that part of said Hingham called Crow Point, conveyed to said Daley by George A. Cole by deed dated March 5, 1929 and duly recorded with Plymouth County Deeds, the right, so far as I have power to grant the same, to use the beach and shore of Hingham harbor opposite the end of Melville Walk and Lot 1 on [the 1897 Plan] for bathing, boating and all proper forms of recreation.

May 1929 Deed (emphasis added).

In sum, at the time of the May 1929 Deed, Daley did not own all of the lots conveyed to him by the March 1929 Deed (i.e., lots A through P). Of those lots, Daley only owned lots A through I in fee simple. Higgins, at that time, owned (at least in equity) lots K through P, which he claim[ed] under Daley pursuant to the April 1929 Deed. The Reeds, at that time, owned lot J (subject to a bank mortgage), which they too claim[ed] under Daley, via Higgins pursuant to the Reed Deed. I am thus called upon to determine whether the fact that Daley owned only lots A through I at the time of the May 1929 Deed defeats that deeds purported grant of rights in favor of lots J through P.

Easements, such as those created by the May 1929 Deed, can be either appurtenant or in gross. Appurtenant easements attach to and run with the land intended to be benefitted thereby (the dominant estate), and benefit the possessor of said dominant estate. Schwartzman v. Schoening, 41 Mass. App. Ct. 220 , 223 (1996). As they attach to the land itself -- not the owner of the land personally -- they are not typically severable from the dominant estate, and thus cannot be assigned or transferred separately from the dominant estate itself. Id. at 223-224. On the other hand, they are presumed to be included in a grant of the dominant estate unless an opposite intent is clearly expressed. Id.

Easements in gross, by contrast, attach to the person of the grantee and are not tied to ownership or occupancy of a particular unit or parcel of land. Restatement (Third) of Property (Servitudes) § 1.5(2) (2000). There is a general presumption favoring appurtenant easements as distinguished from personal easements (easements in gross). An easement is not presumed to be personal unless it cannot be construed fairly as appurtenant to some estate. Denardo v. Stanton, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 358 , 361-362 (2009) (internal citations omitted).

The easement at issue here specifically provides that the rights granted thereby were intended to be appurtenant rights. [Note 56] Even if such intent had not been explicitly stated, it is obvious that an easement to access and use a nearby beach in favor of an inland lot would in some degree benefit the possessor of the land in his physical use or enjoyment of the tract of land to which the easement is appurtenant. Denardo, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 361 (quoting Restatement (First) of Property (Servitudes) § 453, comment b (1944)). [Note 57] Moreover, an easement may be appurtenant to land even though the servient tenement is not adjacent to the dominant, and even though it does not appear what the grantee's rights over the intervening land, if any, may be. Jones v. Stevens, 276 Mass. 318 , 325 (1931). [Note 58] Thus, I FIND that the easement rights granted by the May 1929 Deed were intended to be appurtenant to the dominant estate identified thereby, namely, the land on Downer Avenue and Jarvis Avenue . . . conveyed to [Daley] by [Cole] by the [March 1929 Deed], and not personal to Daley (i.e., in gross).

At the time of the May 1929 Deed, Daley owned lots A through I in fee simple, so each of these lots was clearly a beneficiary of the May 1929 Deed. Defendants no longer dispute this. Accordingly, I FIND that the May 1929 Deed was effective to convey deeded easement rights as appurtenant to lots A through I on the February 28, 1929 Plan, each of which lots comprised a portion of the former lot 3" on the February 25, 1929 Plan. The Kanes, Patrolia and Callahan, and the Arnolds successors in interest (Flaherty and Whelan) all trace their titles back to this group. As such, I FIND that the Kanes, Patrolia and Callahan, and the Arnolds successors in interest (Flaherty and Whelan) are all beneficiaries of the easement rights conveyed by the May 1929 Deed, which are appurtenant to their respective properties. The exact scope of those easement rights is discussed in the next section.

While Defendants now concede that lots A through I received easement rights pursuant to the May 1929 Deed, they still argue that lots J through P did not, because Daley no longer owned those lots at the time of the May 1929 Deed. Notably, this argument runs contrary to the recommendations made by the Land Court-appointed title examiner in the Registration cases, who appears to have considered this issue and rejected it, determining instead that each of the properties conveyed by the March 1929 Deed did in fact receive appurtenant rights pursuant to the May 1929 Deed. It also appears to run contrary to the trial testimony of Defendants own expert witness. [Note 59]

Even if the Land Court title examiner had not rejected Defendants claim as meritless, this court now does. Quite simply, the chain of title defects that were at issue in the cases cited by Defendants (all of which dealt with defects in an easement grantors title) are not present in situations like this, in which there is, at best, ambiguity as to the grantee of an easement. Rather, they apply to situations in which the grantor of an easement purports to grant easement rights that he or she does not have to convey. Here, Daley was merely named as a presumptive beneficiary of the easement rights conveyed by the May 1929 Deed, which were explicitly intended to be appurtenant to the land conveyed in the March 1929 Deed, and which were specifically described as passing to those claiming under Daley.

In essence, Defendants attempt to liken this situation to cases involving easements overburdened by after-acquired property. [Note 60] The fit is not a good one. Moreover, Defendants have failed to cite -- and this court is unaware of -- any authority suggesting that a grant of easement rights explicitly intended to be appurtenant to a specifically-identified dominant estate fails simply because the granting document does not correctly identify the then-owner of said dominant estate at the time of the grant. [Note 61] Rather, where an easement reasonably identifies a dominant estate, [a]n easement is to be interpreted as available for use by the whole of the dominant tenement existing at the time of its creation. Murphy v. Olson, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 417 , 421 (2005) (quoting Pion v. Dwight, 11 Mass. App. Ct. 406 , 410 (1981)). Thus, Defendants chain of title argument fails.

Even if White, the grantor of the May 1929 Deed, had been mistaken about what land Daley owned, the May 1929 Deed references not only Daley, but also those claiming under him as their respective interests may appear as appurtenant to the land . . . conveyed to said Daley by George A. Cole by [the March 1929 Deed]. That land, as noted, supra, was described as lot 3", which was later subdivided by the February 28, 1929 Plan into sub-lots A through P. Had the May 1929 Deed indicated a clear intent to grant easement rights to Daley in gross (or as appurtenant only to the land he owned at the time of the May 1929 Deed), Defendants argument might fare better. However, because the May 1929 Deed does reference other beneficiaries and identifies with specificity the land to which the deeded rights were intended to be appurtenant, Defendants argument, in essence, asks this court to read such language out of the deed. [Note 62]

At most, the fact that Daley, at the time of the May 1929 Deed, no longer owned all of the land conveyed by the March 1929 Deed suggests an ambiguity in the May 1929 Deed. In cases of ambiguity, attendant circumstances at the time of an easements creation must be used to elucidate the grantors intent. See Lowell v. Piper, 31 Mass. App. Ct. 225 , 230 (1991); Hickey v. Pathways Assn, Inc., 472 Mass. 735 , 743-761 (2015) (discussing the great importance of the grantors intent and the lengths to which subsequent purchasers must go in order to fulfil a duty of due diligence, even in the case of registered land); Appeals Court Decision 2, 88 Mass. App. Ct. at 1103, *2. Moreover, even if the language of a restrictive covenant is not particularly ambiguous, restrictions on land must still be construed with a view of avoiding results which are absurd, or inconsistent with what was meant by the parties to or the framers of the instrument. Kline v. Shearwater Assn, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 825 , 831 (2005).

The sequence of events surrounding the conveyances around the time of the May 1929 Deed is illustrative as to Whites intent as grantor of the May 1929 Deed. The March 1929 Deed was executed on March 5, 1929 and recorded a day later. Contemporaneously recorded with the March 1929 Deed was the February 25, 1929 subdivision plan to which it referred, as well as the White Mortgage. The April 1929 Deed was executed just a month later, on April 11, 1929, and was recorded on April 16, 1929 -- contemporaneously with the release of the White Mortgage and with the Daley Mortgage. Two days after that, the February 28, 1929 Plan was recorded. The May 1929 Deed was executed less than a month later, on May 14, 1929. Two days later, on May 16, 1929, the deed of lot J from Higgins to the Reeds was executed, recorded the following day. Four days after that, on May 21, 1929, the May 1929 Deed was recorded.

Based on this rapid sequence of events, it is clear that White, trustee of the Downer Estate and grantor of the May 1929 Deed, was aware that Daley and Higgins were involved in extensive conveyancing of the properties formerly owned by the Downer Estate. [Note 63] Properties were changing hands rapidly, with mortgages granted by and between these parties and discharged soon thereafter. Based upon the documents recorded in sequence on April 16, 1929, it is clear that White specifically knew that Daley had unencumbered title claims in one form or another in all of the lots conveyed by the March 1929 Deed other than lot J. Yet, nothing in the May 1929 Deed itself suggests an intent to differentiate lots A through I (owned by Daley) from J (owned by the Reeds) and/or K through P (owned equitably by Higgins) or to tie the easement solely to Daley, personally. Indeed, the May 1929 Deed does not even acknowledge the subsequent subdivision of the land conveyed by the March 1929 Deed into lots A through P, but instead references the land as it was composed at the time of the March 1929 Deed (i.e., as lot 3").

Even after lot 3" was subdivided, all of the resulting sixteen lots were nothing more than vacant, recently-subdivided lots slated for future development. Thus, given the above-described circumstances (and absent any indication of intent or explanatory attendant facts), it strains credulity to suggest that White would have intended to single out and differentiate some of these lots (J through P) from other, essentially identical ones (A through I) for the purpose of affirmatively denying the former lots the same appurtenant easement rights granted to the latter ones -- all without even acknowledging the subdivision of lot 3" into lots A through P.

A much more plausible explanation would be that White, as trustee of the Downer Estate -- anticipating the imminent expiration of the Indenture, and apparently having realized that the Downer Estate had never explicitly deeded out the fee in the Disputed Beach -- executed and recorded the May 1929 Deed as a means of granting to a parcel of vacant inland lots slated for future subdivision and development the Downer Estates use and access rights (to whatever extent it had them to convey) in the Disputed Beach, which, as the record amply demonstrated, had been used for decades by locals as a community beach.

Thus, given the rapidity with which properties were changing hands, it is reasonable to conclude that, as a matter of convenience, White phrased the Downer Estates grant of easement rights in the May 1929 Deed in such a way as to be appurtenant to all land conveyed by the March 1929 Deed, with the owner of such lots identified as Daley and those claiming under him (whomever that might be), fully expecting that all of the land conveyed by the March 1929 Deed would receive easement rights -- not only the portion of that land owned by Daley at the time the grant was recorded. As such, the fact that Daley did not own the fee in lots J through P at the time of the May 1929 Deed did not serve to defeat the clear intent of White to grant easement rights to those lots. In this way, I thus resolve the ambiguity in the May 1929 Deed, to whatever extent such ambiguity can be said to exist.

Accordingly, I FIND that the May 1929 Deed was effective to convey the same deeded easement rights as appurtenant to lots J through P on the February 28, 1929 Plan (whose owners claim[ed] under Daley), each of which lots comprised a portion of the former lot 3" on the February 25, 1929 Plan, as were conveyed as appurtenant to lots A through I on the February 28, 1929 Plan. The Kanes, Patrolia and Callahan, and the Arnolds successors in interest (Flaherty and Whelan) all trace their titles back to this group. As such, I FIND that the Manns successors in interest (Robin and Cavanaugh) , Ponder successors in interest (the Annellos), Dow, and the Coxes are all beneficiaries of the easement rights conveyed by the May 1929 Deed, which are appurtenant to their respective properties. The exact scope of those easement rights is discussed, infra.

In sum, based upon the foregoing discussion, I FIND that all of the parties defined in Amended Appeals Court Decision 1 as the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs (i.e., the Kanes, the Manns, Ponder, Dow, the Coxes, Patrolia and Callahan, and the Arnolds, or the successors in interest to any of these parties) have such deeded easement rights as were conveyed by the May 1929 Deed. [Note 64] I thus turn to the scope of those rights.

Rights in Melville Walk

Ascertaining the scope of the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs rights in Melville Walk (and the Disputed Beach) requires an interpretation of the meaning of language in the May 1929 Deed. The basic principle governing the interpretation of deeds is that their meaning, derived from the presumed intent of the grantor, is to be ascertained from the words used in the written instrument, construed when necessary in the light of the attendant circumstances. White v. Hartigan, 464 Mass. 400 , 410- 11 (2013).

At the time of the May 1929 Deed, the Downer Estate had already conveyed out all of the properties abutting Melville Walk (other than the Disputed Beach). [Note 65] The May 1929 Deed does not specifically mention rights in Melville Walk. In fact, it does not mention Melville Walk at all other than as a reference to the location of the Disputed Beach. Nonetheless, the Appeals Court found not only that, at the time of its 1929 conveyance of rights to use the beach and the ways, the estate of Samuel Downer held the rights it purported to convey by that instrument, and [t]he [ ] intent of the Downer estate to convey (by means of the 1929 instrument on which the plaintiffs base their claim) the right to use Melville Walk and the beach is manifest by the express terms of the instrument [Note 66], but also that the 1929 instrument validly conveyed rights to use the beach and ways. The Appeals Court accordingly reverse[d] the judgment insofar as it declared that the plaintiffs claiming deeded rights do not hold the right to use the way. Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 750. [Note 67]

Notwithstanding the foregoing, in their brief on remand to this court, Defendants still advance the argument that, even if the May 1929 Deed had been effective to convey rights in the Disputed Beach to (some of) the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs, that deed should not be interpreted as conveying implied easement rights in Melville Walk because, at the time of that grant, the Downer Estate did not own the fee in Melville Walk. [Note 68] Thus, while Defendants now concede that (some of) the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs have rights in the Disputed Beach, Defendants now urge this court to conclude that they have no right to access it by land. [Note 69]

As discussed, supra, however, the Appeals Court appears to have rejected this claim, having held that the 1929 instrument validly conveyed rights to use the beach and ways and thus reversed the Judgment insofar as it declares . . . that the deeded rights plaintiffs hold no easement rights in Melville Walk . . . . Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 759. [Note 70] In any event, even if Amended Appeals Court Decision 1 was not meant as a rejection of Defendants claim, this court now does so. [Note 71]

As noted, the Appeals Court has found that, at the time of its 1929 conveyance of rights to use the beach and the ways, the estate of Samuel Downer held the rights it purported to convey by that instrument. Appeals Court Decision 1 strongly suggests that the Appeals Court believed that this was the case based either on a theory of implication from necessity (the requisite necessity is not an absolute physical necessity, but no more than a reasonable necessity, Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 756 (quotation omitted)), or one of implication based on prior use (evidence of use of a way for access preceding severance of the dominant parcel from the servient way will support the creation of an easement by implication, Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 755). [Note 72] I agree. Indeed, either theory supports this conclusion.

In accordance with the theory of implied easements by necessity:

When the owner of two adjacent parcels of land retains ownership of one and conveys the other by an instrument which is silent as to a right of easement over one of the parcels for the benefit of the other, and such an easement is later asserted in court based upon an open and continuous use by the owner of one parcel for the benefit of the other at and preceding the time of the grant if there is evidence tending to show an intent of the parties at the time of the conveyance that such an easement be then created the question of the construction of the instrument is presented. The existence of such intention must be determined from the terms of the instrument and from the circumstances existing and known to the parties at the time the instrument of conveyance was delivered. There are cases where a single circumstance may be so compelling as to require the finding of an intent to create an easement. For example, if, after a conveyance of some of his land, an owner is left with a parcel entirely surrounded by the land conveyed, the sole fact that he has no access to the land retained without crossing the land conveyed maybe sufficient basis for the implication of an easement although the deed of conveyance contains a warranty against encumbrances.

Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp. v. Holyoke Realty Corp., 284 Mass. 100 , 104 (1933).

In this case, the Downer Estate conveyed out all of the properties abutting Melville Walk one by one between 1897 and 1917. However, it retained the fee in the Disputed Beach all the while.

Additionally, at the time of each of those conveyances, the Indenture was in effect. Thus, at the time of each of the grants of the properties abutting Melville Walk, persons claiming under Downer were using Melville Walk for the purpose of accessing the Disputed Beach. See discussion, supra, n. 72. The Indenture not only gave numerous inland lots rights in the Disputed Beach, but it also created in the Downer Estate an obligation to ensure that access to the Disputed Beach was preserved. See Commercial Wharf E. Condo. Ass'n v. Waterfront Parking Corp., 407 Mass. 123 , 134 (1990) (servient estate may not take actions that unreasonably interfere with dominant estates easement rights). The most feasible way to do so was via Melville Walk. As the 1897 Plan and the Indenture were of record at the time all of the lots abutting Melville Walk were conveyed out, the purchasers of those lots were on notice of this set of circumstances.

In determining whether an easement by necessity should be found, intent, not strict necessity, is the key. Mt. Holyoke, 284 Mass. at 105. Under the circumstances presented, the Downer Estate had clear and obvious reasons to preserve access rights over Melville Walk for purposes of accessing the Disputed Beach at the time each of the lots along Melville Walk were conveyed out, namely, to preserve the Downer Estates reasonable ability to access the Disputed Beach both for itself and by such parties who had rights under the Indenture. Thus, I FIND that the theory of implied easements by necessity supports the conclusion that the Downer Estate had easement rights in Melville Walk to convey at the time of the May 1929 Deed.

The theory of implied easements based upon prior use also supports this conclusion. As recognized by the Appeals Court, an [o]pen and obvious use consistent with a claimed implied easement prior to a conveyance may also be a circumstance indicative of an intent on the part of the grantors and grantees to create such an easement. Boudreau v. Coleman, 29 Mass. App. Ct. 621 , 630 (1990); see also Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 755. As noted, supra, at the time the lots abutting Melville Walk were deeded out, the Downer Estate retained the fee in the Disputed Beach, and Melville Walk was in use by all parties with rights in the Indenture. See discussion, supra, n. 72. The fact that such use was ongoing at the time all of the Melville Walk lots were deeded out suggests that the Downer Estate had good reason to impliedly retain rights in Melville Walk as appurtenant to the land they retained (the Disputed Beach). Thus, the same factual considerations discussed, supra, with respect to easements by necessity also support the conclusion that the Downer Estate would have intended to impliedly reserve easement rights in Melville Walk when it conveyed out the lots abutting Melville Walk based upon the prior use of Melville Walk by the Downer Estate itself and those claiming rights under it. Thus, I FIND that the theory of implied easements based upon prior use, too, supports the conclusion that the Downer Estate had easement rights in Melville Walk to convey at the time of the May 1929 Deed.

In sum, both the theory of implied easements by necessity and the theoryof implied easements based upon prior use support the conclusion, which I thus hereby reach and FIND, that the Downer Estate had access rights in Melville Walk to convey at the time of the May 1929 Deed. I now turn to the question of whether that deed was effective to convey such rights despite its failure to mention them -- in other words, whether the easement rights impliedly reserved by the Downer Estate were impliedly conveyed on to the beneficiaries of the May 1929 Deed.

En route to its conclusion that the 1929 instrument validly conveyed rights to use the beach and ways, the Appeals Court cites the reasoning of the Land Court in the 1922 Registration case pertaining to the Alice Walk Lot, which found that the petitioner in that case (Arthur Harvey) had, by implication, as appurtenant to [the Alice Walk Lot] rights of way in said Alice Walk and Melville Walk Harvey v. Drew, Case No. 21 REG 8311, Slip Op. at 3 (Mass. Land Ct. Jan. 30, 1922). As with the May 1929 Deed, the deed at issue in the 1922 Registration case (in which objections were filed by predecessor owners of the Donahue, Stimson, and OConnell Properties) also did not specifically mention rights in Melville Walk. The court nonetheless found that such rights existed based on the principle that when lands are purchased according to a plan on which streets are shown, the owner acquires by necessary implication a right to use ways thereon shown, which may be available to the beneficial use of his premises. Id.; see also Leahy v. Graveline, 82 Mass. App. Ct. 144 , 147 (2012) (the owner of land may make use of one part of his land for the benefit of another part in such a way that upon a severance of the title an easement, which is not expressed in the deed, may arise which corresponds to the use which was previously made of the land while it was under common ownership. (quotation omitted)). [Note 73]

This principle was recently reaffirmed by the SJC in Hickey, 472 Mass. at 754 ([A] right of way shown on a plan becomes appurtenant to the premises conveyed as clearly as if mentioned in the deed. (quotation omitted)); see also Bos. Water Power Co. v. City of Bos., 127 Mass. 374 , 376 (1879) (a plan referred to in the deeds to the purchasers . . . must be considered as making a part of the contract in each case, so far as is necessary to aid in the identification of the lots, and the description of the rights intended to be conveyed.).

Hickey, like this case, dealt with easements in favor of inland lots over a way depicted in a plan of subdivided land formerly held in common ownership. Unlike in this case, the property at issue in Hickey was registered land. However, even in that context (in which encumbrances not found on a certificate of title are extremely disfavored) the SJC still found that an implied easement did exist, observing that [i]f the land at issue here were recorded land, it is unlikely that this case would be before us. Hickey, 472 Mass. at 737. Rather, in such circumstances (like those presented here), [u]nder long-standing common-law rules of interpretation of deeds containing references to plans, the defendants understanding [that implied easements were created due to the depiction of ways on plans of record] likely would prevail. Id.

Whatever the circumstances, however, whendetermining whether to find animplied easement based upon the depiction of a way in a plan referenced in a deed, the grantors intent is paramount. Id. at 763, n. 35. Thus:

reference to a plan like [the 1897 Plan], laying out a large tract, does not give every purchaser of a lot a right of way over every street laid down upon it. Further, [i]t is well established that where land is conveyed with reference to a plan, an easement . . . is created only if clearly so intended by the parties to the deed.

Jackson v. Knott, 418 Mass. 704 , 711-712 (1994) (quotations and citations omitted); see also Hickey, 472 Mass. at 763, n. 35 (citing Jackson); Pearson v. Allen, 151 Mass. 79 , 82 (1890). Thus, in this case, the mere fact that the 1897 Plan depicted hundreds of lots does not necessarily entail that all of those lots had rights in Melville Walk. Rather, such a determination can be (and hereby is) made only as to whether the specific reference to the 1897 Plan in the May 1929 Deed supports the conclusion that such grant included implied easement rights in Melville Walk in favor only of the specific grantees of that deed.

In determining [such] intent, the entire situation at the time the deeds were given must be considered. Id. at 754 (quoting Goldstein v. Beal, 317 Mass. 750 , 755(1945)). On this question, the case of Reagan v. Brissey, 446 Mass. 452 , 458-460 (2006) offers a factually distinct, though analogous, situation. In Reagan, the court was called upon to determine if the conveyance of lots in a seaside community included appurtenant easement rights to use certain parks and recreational spaces depicted on plans of the area, even though the deeds to those lots did not actually reference such rights. The court found that such rights did exist, noting that such rights may be found based upon the presumed intention of the parties, to be gathered from the language of the instruments when read in the light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or with which they are chargeable. Id. at 458 (quoting Labounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 , 344 (1967)). Such evidence, in Reagan, took the form of plans laying out communal parks and recreational spaces, as well as historical advertisements contemporaneous to the creation of the subdivision at issue. The exact form such evidence takes is not important; what is important is that it definitively shows that an implied easement was clearly so intended by the parties to the deed. Jackson, 418 Mass. at 712.

In the case at bar, as did the deed in the 1922 Registration of the Alice Walk Lot, the May 1929 Deed makes reference to the 1897 Plan, which clearly depicts Melville Way as a means of accessing the Disputed Beach. Further, the properties benefitted by the May 1929 Deed (located inland) were physically separated from the Disputed Beach, which would have been inaccessible to (and thus unusable by) the owners of those lots but for Melville Walk. Indeed, as noted by the Appeals Court, providing access to the otherwise-inaccessible Disputed Beachwas, at the time of that plan, the only purpose for which Melville Walk existed. [Note 74] See Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 755-757 (discussing trial evidence of the use of Melville Walk); n. 72, supra. These circumstances present a strong possibility that an implied easement may have been intended. Further examination substantiates such possibility.

To do so requires taking a view of the history of the Crow Point neighborhood in which these properties are located. [Note 75] As discussed, supra, the properties at issue were all, at one point, owned by Samuel Downer and, after his death, by the Downer Estate. History recalls Downer as a Bostonian, an abolitionist, and an industrialist in the oil and kerosene business, who purchased land in Hingham with plans to build a factory there. After that proved infeasible, in the early 1870s, Downer set about spending lavishly to develop his land as a seaside resort community, with a new wharf (Downers Landing), a lavish hotel (the former Rose Standish House), and an amusement park -- the former Melville Garden (reputedly named for the family of Downers wife, the Melvilles, of Moby Dick fame). In addition to these amenities, Downer began dividing up his property into small lots suitable for residential development by permanent residents, accessed by streets and ways named for friends and members of Downers family. [Note 76] In 1879, Downer entered into the Indenture with Cushing to ensure that the owners of property located inland from the Crow Point beaches retained the right to use those beaches. In 1881, Downer passed away, leaving a will that created the Downer Estate and put his land into trust with instructions for his scheme of development of Crow Point to continue on after his death and for the maintenance of Downer Landing as a public resort. Bos. Evening Transcript, Sept. 21, 1881, supra at n. 2. Melville Garden continued in existence until 1896, and closed only after the death of Downers son-in-law, James Scudder. At or around that time, the buildings at Melville Gardens were razed and the land redeveloped for residential development (part which is today the Schwartz Property, the Stimson Property, and the OConnell Property), and the trustees of the Downer Estate began to further subdivide and deed out all of Downers holdings in the area for residential use, a process that continued for approximately the next thirty years.

In other words, here, as in Reagan, the land at issue was intended by Downer to form a seaside community composed of relatively small lots with recreational spaces used by the community and visitors to congregate and socialize. The former Melville Garden resort was one such space. The area beaches (including the Disputed Beach) were others. The importance of those communal spaces was specifically and emphatically established by the Indenture, which established rights for all landowners, present and future, to use the areas beaches and ways.

Of course, as noted, supra, the foregoing facts should not lead one to think that all of the lots in the area should have rights in Melville Walk and/or the Disputed Beach simply because of the areas history, or because the properties were depicted on the 1897 Plan. Jackson, 418 Mass. at 712. That history serves only as context for the specific grant -- the May 1929 Deed -- as to which this court is called upon to determine whether such rights were, in this particular instance only, specifically intended. Id.

As discussed, supra, at the time of the May 1929 Deed, the Indenture was due to expire imminently, and numerous inland lots stood to lose seaside access rights when that occurred. White, acting as trustee of the Downer Estate, apparently realized that the Downer Estate, which was in the process of divesting itself of all its property holdings in the area, had (perhaps through some oversight) never explicitly deeded out the fee in the Disputed Beach, as it had done with the Alice Walk Beach and the Schwartz Beach. He thus prepared the May 1929 Deed, which purported to grant rights appurtenant to a tract of land slated for future subdivision and development in the Disputed Beach, which, as the record amply demonstrated, had been used for decades by locals as a community beach. White did not specifically mention rights in Melville Walk, but, as trustee, he had them to convey (as found, supra), and, without them, the beach rights granted would have been more or less useless.

In addition to these factual considerations, the fact that the rights granted in the May 1929 Deed were beach rights is critical, as is the fact that an implied easement over Melville Walk would provide inland lots with access (indeed, their only access) to the Disputed Beach. In this context, the Appeals Court has specifically emphasized the importance and obvious benefits of beach rights to inland lots. See Murphy, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 422-423 (finding beach easement rights were implied by an access easement to the beach even though the grantor should have stated clearly that they were reserving rights . . . [and] careful drafting would have avoided the problem because an easement carries with it all rights reasonably necessary for [its] full enjoyment); Labounty, 352 Mass. at 349- 350; Anderson v. De Vries, 326 Mass. 127 , 133-134 (1950); Pearson, 151 Mass. at 82 (access to the ocean was very nearly as important as access to the public streets); Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 756-757 (citing Murphy). These cases suggest that valuable beach rights implicate a need for an especially vigorous application of the general principle that easements must be construed to avoid results which are absurd, or inconsistent with what was meant by the parties . . . . Kline, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 831. Though these cases involve implied rights in beaches arising from easements in ways leading to said beaches, this court can discern no basis upon which to conclude that the converse application would be any different.

In the face of all of the foregoing considerations, Defendants urge me to ignore the rule articulated in Murphy, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 423 (an easement carries with it all rights reasonably necessary for [its] full enjoyment), and instead conclude that it was the intent of White to grant rights to use the Disputed Beach -- which was inaccessible to them by land other than via Melville Walk -- but not the attendant rights to use the only available access way to actually get to the Disputed Beach and enjoy the appurtenant rights therein. Such a reading severely strains plausibility. Just as I declined Defendants invitation to interpret the May 1929 Deed as intended by White to single out some lots in the tract conveyed by the March 1929 Deed and exclude them from the grant, I now decline Defendants invitation to reach the result that White intended to conveybeach easement rights that would have been, on Defendants interpretation, as valuable as they were unusable. Such would be an absurd result, which would, on its face, be inconsistent with what was meant by the parties . . . . Kline, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 831.

Clearly, as in Murphy, more careful drafting would have avoided the problem. Murphy, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 422. Basic principles of prudent conveyancing dictates that White should have referenced Melville Walk in the May 1929 Deed. However, the fact that he did not does not constitute reliable evidence that he intended to withhold easement rights in Melville Walk, since a right of way shown on a plan becomes appurtenant to the premises conveyed as clearly as if mentioned in the deed. Hickey, 472 Mass. at 754.

In view of the foregoing considerations, I FIND that the Appeals Court was correct to state that, not only did the estate of Samuel Downer [hold] the rights it purported to convey by [the May 1929 Deed], Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 757, but also [t]he [ ] intent of the Downer estate to convey . . . the right to use Melville Walk and the beach is manifest by the express terms of [that] instrument, id. at 756, n. 14. As such, I FIND further that the Appeals Court was correct to state that the [May 1929 Deed] validly conveyed rights to use the [Disputed Beach] and [Melville Walk], Amended Appeals Court Decision 1, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 757, to the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs. [Note 77] It now remains for me to determine the scope of those rights.

The first question here is what portion of Melville Walk the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs may use. As held in Land Court Decision 1 (and affirmed in Amended Appeals Court Decision 1), the Prescriptive Rights Plaintiffs (Dillon, Campbell, Handrahan, and the Murrays) have established prescriptive rights only over the southerly half of Melville Walk (formerly used as a common driveway and marked by dirt tire tracks), because the evidence at trial was that these parties only actually used that part of Melville Walk for access. [Note 78]

With respect to the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs, however, the matter is somewhat more complicated, as their rights are deeded rights, not prescriptive rights. Unfortunately, the May 1929 Deed is unhelpful on this point, since, as noted, supra, it is silent as to rights in Melville Walk. However, under such circumstances:

It is well settled that when an easement is created by deed, but its precise limits and location are not defined, the location and use of the easement by the owner of the dominant estate for many years, acquiesced in by the owner of the servient estate, will be deemed to be that which was intended to be conveyed by the deed. We think that the same principle is applicable in determining the scope of an easement created by implication.

Labounty, 352 Mass. at 345 (quotation omitted).

As noted, supra, the trial evidence by all parties was unspecific as to which part of Melville Walk was used by the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs. However, in Land Court Decision 1, I found that, because the northerly half of Melville Walk adjacent to the Donahue Property had been grassed over and used as a lawn for that property for decades (more recently being fenced in), and because no evidence in the record tended to suggest that any parties were using this lawn area for passage, the most reasonable inference was that the only use of Melville Walk for access to the Disputed Beach was via the northerly side of Melville Walk -- i.e., the common driveway marked by tire tracks. The Appeals Court affirmed this determination. I see no reason now to grant greater rights to the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs. Moreover, the evidence at trial showed that access rights only in the southerly portion of Melville Walk is more than adequate to enable the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs to access the Disputed Beach for the purposes (discussed infra) for which they may use it. See Rajewski v.

McBean, 273 Mass. 1 , 6 (1930) (When a right of way is granted but its exact limits are not defined in the deed, the grantee is entitled to a convenient way within the land specified adapted to the convenient use and enjoyment of the land granted for any useful and proper purpose for which it might be used considering its location and all circumstances.). Thus, I FIND that the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs access rights via Melville Walk are limited to the full length of Melville Walk from Downer Avenue to the Disputed Beach, but only on the southerly half of Melville Walk (i.e., the side adjacent to the OConnell Property, the Stimson Property, and the Schwartz Property). [Note 79]

I thus turn to the actual scope of those rights, i.e., what actual uses the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs may make of the southerly half of Melville Walk. As this court and the Appeals Court have both found, the purpose of Melville Walk, at the time of the May 1929 Deed, was only to enable passage from Downer Avenue to the Disputed Beach. [Note 80] The evidence adduced at trial bythe Plaintiffs (both those claiming deeded rights and those claiming prescriptive rights) was that they used Melville Walk to access the Disputed Beach by foot. In doing so, numerous parties testified that they used Melville Walk to transport small boats by pulling them down Melville Walk in carts or by having heavy boys (to quote Mrs. Dillon) carry them down. None of the Plaintiffs testified that they ever used Melville Walk to access the Disputed Beach by car or truck. [Note 81] Moreover, nothing on the face of the May 1929 Deed suggests that the grantor intended Melville Walk to accommodate vehicular traffic by the grantees of that deed. Thus, I FIND that the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs may use Melville Walk for pedestrian access, but not vehicular use. [Note 82]

Further, I FIND that, based upon the evidence of use in the record, as well as my interpretation of the May 1929 Deed (and the presumed intent of the grantor of that deed), the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs [Note 83] are entitled to use the southerlyhalf of Melville Walk solely for the purpose of accessing the Disputed Beach for the purposes of availing themselves of the rights specified in the May 1929 Deed, namely, bathing, boating and all proper forms of recreation. I FIND further that the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs may not use Melville Walk for parking or storage, to build permanent structures, or to run utilities lines. Further, I FIND that Defendants may not take any action inconsistent with the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs herein-declared rights in Melville Walk. Highland Club of W. Roxbury v. John Hancock Mut. Life Ins. Co., 327 Mass. 711 , 714-715 (1951) (The owner of a servient estate may make such use of his land as is consistent with the easement of another, . . . but the corollary of that rule is that he may not use his land in a manner inconsistent with the easement.). Thus, I FIND that, to the extent Defendants have erected gates, fences, walls, furniture, or other barriers or impediments to access to the Disputed Beach via the southerly half of Melville Walk, they shall be removed forthwith.

Rights in the Disputed Beach

Finally, I turn to the scope of the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs rights in the Disputed Beach. The May 1929 Deed defines the uses for the Disputed Beach as bathing, boating and all proper forms of recreation. As Judge Trombly has observed:

An easement for bathing and boating is in the nature of a recreation easement, primarily to provide access to a body of water in order that the user might, as the name suggests, bathe and boat. The beach or shore of the servient estate provides a harbor of sorts, from which this activity may launch and land. The right to boat does not imply rights to erect structures on the waterfront property, no matter how associated with boating it may be, because such structures are, generally, not necessary to the full use and enjoyment of such an easement.

Town of Nantucket v. Lerner, 17 LCR 220 , 224 (Mass. Land Ct. Mar. 31, 2009). [Note 84]

For present purposes, bathing would thus seem to be more or less synonymous with recreational swimming. It includes the right of persons to swim in the water adjacent to the Disputed Beach for pleasure or exercise. It does not include the right to manifest any permanent presence on the Disputed Beach, such as constructing a bath house or changing room.

The term boating denotes a transient activity that would not normally create a spatial or physical obstruction to the boating of others; whereas the mooring or tying of a boat to a structure is stationaryand of longer duration and necessarily creates a barrier to the boating and mooring rights of others entitled thereto. Davis v. Zoning Bd. of Chatham, 52 Mass. App. Ct. 349 , 364 (2001); see

also Wellfleet v. Glaze, 403 Mass. 79 , 87 (1988) (boating is interchangeable with navigation) Under this standard, the term boating would include using the Disputed Beach to launch boats into Hingham Harbor and to bring them back ashore, but would not allow the docking, mooring, or other storage of a boat in the area of the Disputed Beach. [Note 85]

The phrase all proper forms of recreation is more difficult to parse because it involves not merely defining recreation but also applying that definition in the context of beach use. Case law has referenced uses such as usual beach activities [like] placing . . . a beach towel or chair on the sand and the sitting thereonto sunbathe or read with friends, building sandcastles, collecting seashells, playing ballgames, swimming, boating, and walking. Houghton v. Johnson, 14 LCR 442 , 443 (Mass. Land Ct. Aug. 9, 2006) (Long, J.), affd, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 825 (2008). Local bylaws and ordinances also often provide guidance to define recreational uses. Whereas Massachusetts, unlike most states, does not specifically define recreational uses in its Massachusetts Recreational Statute (G. L. c. 21,

§ 17C), the Town of Hingham, in Section 6 of its Wetland Regulations Conservation Commission bylaw, defines recreation as:

Activities that shall be considered part of the use and enjoyment of our natural surroundings in a manner consistent with their preservation shall include but not be limited to recreational boating, swimming, fishing, shellfishing, nature study, painting and drawing, aesthetic enjoyment, walking, [and] hiking. [Note 86]

All of these recreational uses are consistent with the uses to which Plaintiffs testified during the trial, namely boating, swimming, sitting, wading, walking, skimming stones, walking a dog, socializing, and playing. Defendants argue that such uses are not consistent with the terms of the May 1929 Deed; however, they do not argue persuasively against any specific use argued-for by Plaintiffs, nor do they make any attempt to define what recreational uses should include. It does not appear to this court that any such uses are inconsistent with the term all proper forms of recreation.

In sum, I FIND that the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs may use the Disputed Beach for uses consistent with the uses established [at trial] over the last quarter to half century, including launching and landing small boats, swimming, wading, walking, sunbathing, sitting, reading, skimming stones, playing, dog walking, and socializing. [Note 87] I FIND further that the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs may not use the Disputed Beach for vehicle parking, to build permanent structures, for permanent storage, or to run utilities lines.

Conclusion

Based upon the foregoing discussion, this court has determined that all of the Deeded Rights Plaintiffs have rights in both Melville Walk and the Disputed Beach, and has ruled as to the scope and limitations upon those rights, as well as what Defendants must (and may not) do in view of those rights. A Third Amended Judgment to that effect shall enter of even date hereof.

SO ORDERED.

exhibit 1

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] This is the original caption of the case, per Land Court practice. As discussed, infra, a number of the parties to the case have been substituted by successor owners over the twelve years this dispute has been pending.

[Note 2] At times, this court will refer to the historical background of the area solely as a means of giving a context to this dispute and humanizing its cast of characters. However, the courts final determinations are not based upon anything not contained in the trial record. For such historical information, see, e.g., Recent Deaths: Samuel Downer, Bos. Evening Transcript, Sept. 21, 1881 at 2; Sweetser, M.F., Kings Handbook of Boston Harbor, Boston: Moses King Corp. (1888) 81-83; Murphy, J.F., Tourists' Guide to Down the Harbor, Hull and Nantasket, Downer Landing, Hingham, Cohasset, Marshfield, Scituate, Duxbury, "the Famous Jerusalem Road," "Historic Plymouth," Cottage City, Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, and the Summer Resorts of Cape Cod and the South Shore of Massachusetts, Boston: J.F. Murphy, Pub. (1890) 26-28; History of the Town of Hingham, Massachusetts, Vol. 1, Part 2, Town of Hingham (Mass.), Pub. (1893) 250; Hingham: A Story of Its Early Settlement and Life, Its Ancient Landmarks, Its Historic Sites and Buildings, Old Colony Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution, Pub. (1911) 62, 92-93; A Word for Melville Garden, Bos. Evening Transcript, Jan. 18, 1897 6; see also Mass. R. Evid. § 201(b)(2).

[Note 3] The Disputed Beach refers to the same area defined in my prior decisions as the Beach. I adopt this new term in order to avoid confusion with several other nearby beaches that were relevant to this case at trial, namely, the Schwartz Beach and the Alice Walk Beach, defined infra. As discussed, infra, I also attempt to clarify the definition of the Disputed Beach to increase precision as to its exact location and boundaries. Also of note, my prior decisions make reference to a North Beach, a separate beach located on the opposite (northerly) side of the peninsula that is Crow Point, which has nothing to do with this dispute.

[Note 4] A fuller recitation of the facts can be found in my prior decisions and orders.

[Note 5] The major area of reversal was that the Appeals Court found that the Downer Estate, as hereinafter defined, was the owner of the Disputed Beach.